Juliana Read online

Page 6

“I’m afraid there aren’t many artists, writers, or freethinkers in this area anymore. You may have arrived a decade too late.”

“Yeah, I do things like that. Oh, but I still like it here. I doubt I would have been very good at being a bohemian anyway.”

“Over there.” She pointed at University Place. “The Cedar Bar. It’s a pretty rowdy place with a lot of drunken men who fall into the street. You shouldn’t go anywhere near it. It’s dangerous. I know something you’d like to see. Let’s go through the park. It’s nicer that way.”

We passed through Washington Square Park and out to the other side. As we hurried toward Fifth Avenue, I heard a couple of girls giggling as they climbed out of a basement. Then, when I looked closer, I saw they had to be boys with high voices. They started kissing each other and that made me trip over Juliana’s feet. “What are you looking at?” She laughed.

“Them.” I pointed at the two boys. “They’re kissing. Two boys!”

“Shsh. And they’re two girls.”

“No kidding? Those are the kind that Aggie warned me about. The kind that hurt children and capture people. What kinda place is that?”

“Nothing you need to know about right now. You’ll like this next thing I’m going to show you.”

She hurried me away from that strange place, and we crossed Fifth Avenue, then Sixth, and Seventh. We passed brownstones and townhouses and small cafés. We walked down dark shadowy streets with trees so thick they blocked the light from the street lamps. The heat still hung wet in the night air.

“Aggie and Dickie—they’re my friends from Huntington, and we came here to go on the stage,” I told her. “We’ve been planning it since elementary school. We talked about it every day in the lunchroom.”

“Really?”

“Yeah, and Danny came here to be a writer.”

“Danny’s your beau?”

“Yeah. Aggie and Dickie want to do musical theater, and I used to, too, but now I think I’m changing my mind. I always loved reading Shakespeare, and Chekov, and Molière, and writers like that, so I’m thinking maybe that’s the kind of acting I wanna do. Except I saw Lady in the Dark and that was so wonderful—maybe I should do that. Oh, I don’t know. Aggie auditioned for a few radio programs; she’s waiting to hear, and I auditioned for a small part on Broadway, but … I ran away.”

“Did you?”

“Yeah. I’d never been on a stage that big before. Everything got blurry when I tried to read the sides, so I ran away. Miss Haggerty, my drama teacher, who was really my English teacher, would be so disappointed in me. But I’m gonna study with Mrs. Viola Cramden starting in October. Her ad in the Long Islander said she could turn anyone into a Shakespearean actor. Have you ever heard of her?”

“No. I haven’t. Here we are,” Juliana said, stopping in front of a dusty old brick building with a red awning. “The Cherry Lane Theater.”

“Really? This was started by Edna St. Vincent Millay and the Provincetown Players. Oh, I love her play Aria da Capo and Eugene O’Neill was a founding member too. I read Mourning Becomes Electra . It’s a wonderful play. I can hardly believe I’m standing where all those great writers and actors and thinkers once walked.”

“Perhaps someday you’ll appear here.”

“Yes,” I said, staring at the Cherry Lane Playhouse sign. How could this woman who I barely knew have so much faith in me? When I told my mother my plans, she laughed.

“So why theater?” Juliana asked as we started to walk again. “Was it just reading Shakespeare and the rest that convinced you that was what you wanted to do?”

“It was Katherine Cornell. I’ve been reading the classics since grade school, but it was seeing a great play with a great actress saying the words that made me want to get up on stage and do it, too. When I was ten, my nana—she’s my grandma on my father’s side, but I got along better with my grandma on my mother’s side—took me to Albany to see Katherine Cornell in the Barretts of Wimpole Street for my birthday. Nana’s the only one in the family who had money ’cause she started her own restaurant in New Jersey after her husband left her. She had four boys to raise, one of them my father. Everyone thought she’d fail. You know, a woman running a business, but she was a big success. She helped our family through the Depression by buying me some of my school clothes so I didn’t look like a ragamuffin, but she didn’t get along with my mother. Then she died and things got really hard ’cause she didn’t leave our family any money ’cause before she died she had a fight with my mother. Then my mother started making all my clothes, but she was no good at sewing. But Katherine Cornell—oh, my, I never experienced anything like that before in my life. It was the best thing in the whole world until I saw Gertrude Lawrence in Lady in the Dark . But do you wanna know what I really wanna do?”

“Tell me.”

“Something completely absolutely wonderful. Only—I don’t know what that is yet. Maybe it’s acting in great plays, but it might be something else. I don’t know. I decided I had to do something absolutely completely wonderful when I was eight years old. Whenever my mother threw me out of the house and locked the door so I couldn’t get back in—”

“What?”

“It was okay. It helped me think. I’d walk around the block or hide under the porch, and that’s when I thought I had to do something absolutely completely wonderful with my life. Only … I’m still trying to figure out what that is.”

“Well, this is my place,” she said. We stood in front of a large brownstone that had flowers in a ceramic pot sitting on one of the steps. I’d been talking so much I hadn’t noticed that we’d turned around and crossed back over Seventh, Sixth, and Fifth Avenues. “Will you come up for a cup of tea?” she asked.

That’s when I thought about time. “No!” I shouted, looking at my watch. I ran as fast as I could. I only had nine minutes to make Mrs. Minton’s curfew. Oh, God, oh God, don’t let me get kicked out. My legs ached with beating against cement sidewalks. I couldn’t imagine what Juliana must think of me. I was Cinderella about to turn into a wretched old hag eating a chewed-up chicken leg out of a garbage can.

As I ran up the steps to Hope House, Mrs. Minton stood at the door ready to close it, her eyes glued to her watch. I dashed past her and skidded to a stop in the foyer. Without a word, Mrs. Minton locked the door and walked into the parlor. I leaned on the banister catching my breath, my program locked in my grip. One time my father cried when my mother locked me out of the house. The program was slightly creased from squeezing, so I laid it on the small table near the stairs and carefully smoothed it out. Later, I kept it on my dresser under War and Peace so it didn’t get torn.

Chapter Eight

August, 1941

The summer wore on, hot and oppressive, as we settled into our New York lives. Aggie had two lines in a Post Toasties commercial on the radio and for a while she had a job posing for pictures for the Montgomery Ward catalog. I pictured my mother sitting on the couch in the parlor, listening to Jack Benny on the radio, and thumbing through the catalog. She’d smile when she saw Aggie in there. I wished there was something I could do to make her smile.

Most nights I’d come home from work and collapse on my bed listening to Amos and Andy . I’d read Variety , circling the names and addresses of theater managers I should get to know. The next day I’d go to one of their offices during my lunch hour. The trouble with that was my lunch hour was their lunch hour too, so I never got to see anyone. I just knew there had to be a better way to do this, but I didn’t know what that way was. After a while, I stopped going to theater manager’s offices and just ate my cheese sandwich on a Bryant Park bench and reread Wuthering Heights.

One day, this girl who typed on the typewriter in the center aisle, third row, sat down next to me on the bench. “I liked that book,” she said.

We had never talked before. In truth, I hardly ever talked to anyone at work ’cause I had to pretend that the typing pool wasn’t really part of my lif

e. I’d go there and work from nine to five like I was sposed to, but I’d turn myself off, almost like I had a button for doing that, and pretend I wasn’t there. The typing pool couldn’t be my life. It was too much like my father’s life. He went to some job—who could keep track of which one; he had a string of them—but it was always ’cause it was what he had to do, never what he wanted to do. Then he’d come home again and fall asleep on the couch. That is, when my mother let him. When she wasn’t crazy and yelling at demons or cutting herself up or chasing me, then he could fall asleep on the couch. He deserved it, but I didn’t want his kind of life. So I pretended I wasn’t working in the Home Insurance typing pool. Instead, I’d see myself on the stage reciting Shakespeare or flying up in the clouds like Peter Pan or a seagull. And I’d be surrounded by the most beautiful, wonderful music. Like God was singing to me through the clouds, and I’d forget I was really sitting at station five, fourth typewriter from the left, two over from center. Pretending things also helped me to not think about Mr. Johnson, our boss, who sometimes pinched my behind. That was just something we girls had to put up with. So I didn’t really know this girl who sat beside me on a bench at Bryant Park telling me she liked Wuthering Heights , too. I vaguely recalled her sitting one row over and two seats up from mine.

“Out of all the books I’ve read, Cathy’s my favorite character,” the girl said,“ ’cause she had a free spirit in her. Too bad she had to marry that dullard, Edgar. He couldn’t understand her. She should’ve run free over the Moors by herself.”

“Or she could’ve married Heathcliff. He was dark and mysterious.”

“Yeah, if she had to get married to someone, he would’ve been better than Edgar, but I think she would’ve been happier staying single, by herself.”

“But no one in the society would’ve accepted her as an old maid.”

“Cathy is all spirit,” the girl said, like she knew her personally. “She can’t hold herself back from her true nature, but all the people in her life keep trying to make her do that. Edgar loves her, but Cathy has to give up too much to be with him.”

“But it was her choice to marry him.”

“’Cause she wanted fancy dresses and a house. But her true spirit rises above all that. Her free spirit. That’s why she dies at the end, you know. ’Cause of these people stealing away her spirit. She finally can’t take it anymore so she has no choices left; the fine things become burdens that weigh her down; she has to die. That’s the only way she can be her free self.”

“I think maybe Cathy’s a lot like my friend Aggie. She’s filled up with spirit, too. People sometimes think she’s a bad girl ’cause of that, but she’s not.”

“This Aggie is—is your friend?”

“Yeah. We’ve known each other ever since she moved into the neighborhood when she was two.”

“So you’re friends. That’s all. Friends.”

“I think that’s a lot. Friends are important. More important than anything.”

“You’re right. They are.” Her eyes were a sharp blue, and they seemed to be looking right into me.

“Hey, you want half my cheese sandwich?” I asked.

“No. I can get my own. I don’t wanna take your lunch.”

“But I’m not gonna finish it. Here. Have it. ”

She smiled the nicest smile at me, like I was giving her something wrapped in gold instead of wax paper.

The next day, I got excited for work for the first time. I wanted to see her again and talk about books. I hadn’t had a friend to talk about books with since Marta, the Jewish girl I tried to find a loophole for by reading the Bible beginning with Genesis. I was thirteen, and sometimes I’d go over to her house and eat dinner with her family. I liked that, especially when my mother was locked in the asylum or was home being crazy. Her mother and father were awful nice to me, but I liked her mother best. She served food I’d never heard of before, like something called gefilte fish and borscht. I liked the fish, but not so much the borscht, but that didn’t matter ’cause her mother was so sweet to me. Once she even gave me some dessert pies to bring home to my family. She called them, uh, uh blintzes, and they kind of tasted like cherry pie. I didn’t tell her my mother was in that place. Her family was too nice for God to not let into heaven, so I was sure He put a loophole in His book somewhere.

I looked out over the typewriters. There seemed to be hundreds of them all looking gray and sad, each one with a girl typing out a rhythm. Plunk, plunk, plunk. There was a swelling of joy inside me. I wouldn’t be eating alone anymore.

Only thing, as I sat down at my own station sliding my gloves and hat off, putting them in the cubbyhole next to the typewriter, I didn’t see her. Her station was empty. I thought maybe she’d come in late, but she didn’t. When all the girls were getting out their handbags to go for lunch, she still wasn’t there. She wasn’t there the next day or the next or the next. Then a new girl came in and sat in her place. It was strange ’cause I didn’t even know the girl who liked Wuthering Heights as much as me, not even her name, but I started calling her Cathy in my mind. My heart sank down when I realized she wouldn’t ever be coming back again. The girl who took her place left with the others to go to lunch, and I must’ve stood there staring at the empty typewriter station ’cause this older girl came up behind me pulling on her gloves, getting ready to go out.

“Did you know her?” she asked.

“No. Well … maybe sorta. A little.”

The older girl signaled me to go into the restroom with her. She checked under the stalls to be sure we were alone and then pulled me over by the sink.

“She killed herself, ya know,” she whispered. “Jumped out of her tenth floor apartment window.”

“No!” A pain stabbed me in my chest. “Why would she do that?”

“You didn’t know?”

“Know what?”

The girl looked around the room, making sure no one had come in. “She was … funny.”

“Huh? ”

“One of those girls who … you know, with other girls.” The older girl took a cigarette from her handbag, lit it, and leaned against the sink. “I never heard of her trying anything with anyone in the typing pool, but everyone knew. Except you, I guess. Maybe she did try to convert someone here. I don’t know. Maybe there’s another one of them running around. I’ll tell ya something, though. If a pervert ever tried anything with me, I’d show her a thing or three. Look, I know it’s sad, a young girl doing that to herself, but really, what kind of choice did she have? She had that sickness. If she didn’t do it to herself, who knows what she would’ve done to any of us or to some poor kid?”

“I didn’t even know her name,” I choked out.

“Mary O’Brien.”

I followed Juliana’s career in Cue as best I could, wishing I could go to the club where she was appearing. But I never had an escort with Danny working on his novel.

I had the dream again. But this time Mary O’Brien was in it. It was the one where I dreamed I grew a beard during the night. Usually in the dream I’d look in the mirror and see I’d grown the beard. This time, I didn’t look in the mirror. I looked at Mary O’Brien smiling at me and nodding like she thought the beard looked good on me. It was so real, like Mary was really right there in the room with me, and the hair was thick on my cheeks, chin, and upper lip. It scared me right out of my head. I jumped out of bed and headed toward the mirror to be sure it wasn’t true, but I stopped myself ’cause I didn’t like looking in mirrors. I felt my face instead; it was smooth as always and Mary was gone.

One Saturday in early August, Danny and I went to Coney Island. I’d never been to an amusement park before. In Huntington, we had church fairs and sometimes the circus came, but there were never any amusement parks. Danny and I walked the boardwalk holding hands. There was the smell of popcorn, children running with balloons, and the sound of the Cyclone, the biggest roller coaster in the world, going round.

“Hey, try your luck,

” a barker called to us. There was a bunch of balloons tacked onto a board that you were sposed to burst with a dart. “Try your luck, sonny,” he said to Danny, smiling around his cigar. “Win your girl a kewpie doll.”

Danny tried, but we didn’t win anything. That was okay. Feeling the sun on my head, wearing my new pleated shorts—allowed on the beach—and listening to the sound of the ocean hitting the beach was enough for me. Danny was so much more relaxed that day than all the other days we’d been in New York. We bought Nathan’s Famous franks and sat on the bench squinting at the crowds jumping in the waves as they hit the shore.

“How’s your novel going?” I asked in between bites of my frankfurter.

“Let’s not talk about that.” He grinned, wiping mustard from his chin with a napkin. He put his arm around me. “I don’t even want to think about that today. It’s just good to be with you now, the way we used to be. Have you been going to a lot of auditions?”

“Oh, brother, no. I did for a while, but then I’d get so scared I couldn’t see the words in the script.”

“Keep going. The more you do it, the easier it’s gonna get.”

“I spose. That’s the thing I don’t wanna talk about today.”

We laughed. It was good to be laughing with my friend again.

“Look, Danny, the seagulls. Can you hear them? They’re way out over the ocean so the sound is faint, but if you listen close, in between the splashing waves, you can hear them. The sound is barely there … but—”

“You always notice sounds before anyone else.”

“I love sounds. Not all sounds. Like thunder. I hate that one. But there are so many sounds in the world that grab you by the throat, shake you, and yell, ‘Hey, there! Pay attention to me.’“

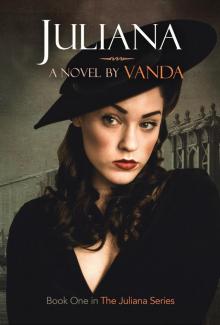

Juliana

Juliana![[Juliana 02.0] Olympus Nights on the Square Read online](https://i1.freenovelread.com/i/03/11/juliana_02_0_olympus_nights_on_the_square_preview.jpg) [Juliana 02.0] Olympus Nights on the Square

[Juliana 02.0] Olympus Nights on the Square